A recent episode of the excellent Radiolab Podcast, Smile My Ass, told the story of Allen Funt, the brains behind Candid Camera. Having created the hit show Funt was nearly hoisted by his own petard when a plane he was travelling on was hijacked in mid-air. Once his fellow passengers recognised the star they became convinced they were participating in a stunt for the programme – and no amount of protestation by Mr Funt would persuade them otherwise. When the hijackers left the cockpit to see what all the commotion was about, many broke into applause. The terrifying reality only became apparent when the plane landed in Cuba, greeted by a military escort.

Since then ‘Reality TV’ has been the fastest growing television genre, blurring the lines further between television and the every-day, and it has since given birth to first parody (The Office, Veep, People Like Us) and now its strange step-child, the ‘Structured Reality’ show. But aren’t all documentaries really ‘structured reality’? From the trashiest shock-doc to the highest investigative journalism filmmakers cut out context, emphasise some facts more than others, amp-up tensions for dramatic effect and work to shape their story in a certain direction. All edited content, by definition, represents a particular ‘take’ on its subjects – so how can we trust what we see? And is that question even important?

Of course, a film-crew doesn’t just interfere with reality in the edit. Their mere presence can have a massive effect on the behaviours of everyone in front of the cameras. On TV documentaries and ‘reality shows’ it is not uncommon for the production crew to take over a subject’s home during the long days of shooting, sleeping on the sofa, breakfasting in the kitchen and destroying completely any sense of normality. Stress levels are high – causing some people to clam up and others to do the exact opposite. Whatever the result, the presence of a crew remains a key but unexplored component of the narrative.

Add to this the growing complicity of the participants and the idea of a ‘reality’ show becomes even more ludicrous. We are all so schooled now, through television and even more so by social media, of constructing an image that we want to project to the world. When we made our ‘real’ documentary web series, I Gotta Be Me (about a frustrated soap star who joins a Rat Pack tribute act) it was fascinating to watch the way people behaved differently as soon as the red light of the camera was on. Some of the participants talked openly of ‘good TV,’ and were aware that ‘good TV’ often included people making fools of themselves. Perhaps because they were all entertainers by trade, but as soon as we pressed record everyone became a bit of a performer. To this day I am unclear whether some moments were ‘real’ or were solely for our benefit…but I am certain they would have played out differently had we not been filming.

Against all this it is no surprise that ‘authenticity’ is the watchword of the second decade of the 21st century. We are seeing the thirst for it in everything from politics and architecture to the branding of coffee. As a mischievous counterpoint, artists are taking increasing pleasure in playing with our need for the ‘real.’ In film and television ‘Paper Heart’, ‘I’m Still Here’, ‘Borat’ and the recent web-series ‘Supreme Tweeter’ all play on the zig-zag lines between fact and fiction, invention and reality. In this type of work film-makers have difficult choices to make regarding their responsibility, or not, to reflect real people and situations ‘accurately.’

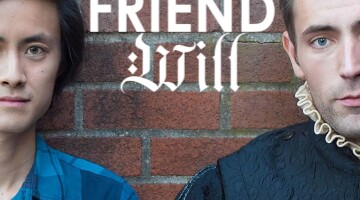

In ‘I Gotta Be Me’ the situated is complicated by the fact Phaldut Sharma (an actor who has appeared on stage and screen with roles including Eastenders, Gravity, Children of Men and The Office) is ‘playing’ the role of Paul Shah. But when an actor is improvising – particularly when they are playing someone so close to themselves – is it possible to claim the results are definitely a work of fiction? Phaldut and Paul share a near identical backstory, and when ‘Shah’ talks about his love of Sammy Davis Junior, or his early experiences winning dance competitions, or his career as an actor, often the only difference between character and actor is how he communicates, not what he has to say. And yet who doesn’t communicate differently when there’s a microphone around? It would certainly be unfair of us to claim that Phaldut was acting but everybody else was 100% ‘themselves.’ For one thing they are all impersonators by trade, so they spend most of their time being somebody else anyway!

The ethical considerations of representing people on screen ultimately come down to the film-maker’s personal choice. ‘I Gotta Be Me’ is not an ‘accurate’ portrayal of everyone involved, and it didn’t set out to be. I’m not sure such a thing would be possible, but even if it were I question whether it would be desirable? Given we have over 180 hours of footage there are a hundred ‘accurate’ stories I could tell of the people and events we filmed in Cyprus, so the question becomes – what story do we want to tell? We decided to celebrate the playful community of performers we met out in Cyprus, and the Las Vegas legends that they draw their inspiration from. In the process we turned our cameras towards moments of silliness and tension, sure, but likewise we turned them away from things that felt too intrusive, too personal, too much like gossip. In the edit we have used the same tool-kit as any documentary maker would do. The result is a curious blend of fact and fiction, suntans and swing. It plays like a sit-com, but I promise you it’s as ‘authentic’ as 99% of ‘reality TV.’

Which isn’t saying much.

No Comment