When I signed on as the executive producer in 2015 for the Coffee House Chronicles web series written and directed by Stewart Wade, who had directed and found distribution for the feature films Coffee Date, Tru Loved, and Such Good People, I realized early on that it was going to be a combination of marathon and sprint. The marathon was the series itself, which in our case was episodic and thus featured new sets of characters each time. So we had to think, like all web series creators do, of the long game and what the series would look like when it was finished.

Director Stewart Wade and crew capture Alex Genther, Dalila Ali Rajah, and Luis Selgas in a scene from Coffee House Chronicles: The Movie. Photo by Tommy Wu Photography.

Because we didn’t have stories that continued from episode to episode, each day-long shoot was like shooting a mini-movie. And that’s where the sprint came in: Stewart and I had to line up new sets of actors and sometimes crew for every single episode, and Stewart had to direct each episode, sometimes months after the last one, to keep a consistent look and tone for the series.

As we got distribution for the web series, first on YouTube and then on the LGBT channel REVRY, we realized that our audiences were sometimes forgiving. There were a couple places where sound was not perfect and where, if we’d had more time, we could have smoothed out some visual transitions. But that seemed to have no bearing on whether people liked an episode or not. Viewers tended to respond to the story and the actors. And in our case, sometimes high responses could be based how much skin the lead male actors were showing, because viewer data confirmed what we’d strongly suspected all along, that gay men made up a healthy part of our viewing audience.

Once we launched the last episode of the web series in August 2016, Stewart and I sat back for a while and watched what seemed to drive more viewers and fans to particular episodes. Some of the episodes had viewership in the tens of thousands and some barely over a thousand, and we chalked most of that up to demographics. Case in point, our stories with women as their focuses unfortunately didn’t get as large viewership as stories with men front and center: again, the gay male audience at work. The lesson we learned is that we could craft the best written, acted, and photographed episode and our viewers would not pay as much attention to it if they felt it wasn’t “on brand.”

Actors Mark Cirillo and Damian Pelliccione meet-cute as zombies in Coffee House Chronicles: The Movie.

Stewart and I started thinking, Wouldn’t it be excellent if we could get our audiences to watch the whole integrated story at once instead of skipping content that we think is terrific?

Well, here’s a news flash: That never happens. Technology offers so many ways for audiences to get exactly to the content they want, and whether it’s deciding which episode to click or deciding what to watch on 8x fast forward, modern viewing audiences are entirely self-determined about what they want to see and in what quantities.

But that idea of integrated content did not go away. So in 2016 I cut together the episodes with some B-roll that I shot on a small camera around my neighborhood. I showed it to Stewart and then to the one audience I knew would sit through the whole thing: my family. We had a small reunion in 2016 and I played the whole draft movie on my laptop for my brother, sister, and brother-in-law. My husband had already seen the whole thing and was allowed to sleep through it, although to his credit he didn’t. My mother drifted in and out of the room, sometimes changing the subject loudly if anything remotely homoerotic appeared on screen.

At the end of it, my family thought it was good, which maybe they hadn’t expected to. But my sister made a comment: The sequence needed something to wrap the whole story together. I thought, Of course it does!

Patching together a bunch of self-contained web series episodes does not a feature film make, no matter how artfully the patching is done. Film audiences expect a beginning, middle, and end unless the whole point is a shorts compilation. So I brought that feedback to Stewart and he wrote two new scenes, one for the beginning and one for the end of the film. He related those scenes to what had been the last episode in the web series, so there would be a throughline.

We had a fun time shooting those new scenes in a coffee shop and at our previous set, which was Stewart’s friend’s apartment. Once we cut it together we could see the piece working better as a movie. Even though it didn’t have interacting characters among all the scenes, which had been the episodes, the film functioned as a kind of smorgasbord view of LGBT Los Angeles with a few characters introducing the action then wrapping it up.

When we started finalizing the film, we spent the money to smooth out the audio and color correction. As people follow a web series they aren’t necessarily noticing that skin tones may look different episode to episode, but in a film something like that can be glaring. Also, we wanted the sound quality to be more even than our web series had been. Once we cleared those two stages we believed we had a marketable film. And the cinematographer Daniel Watchulonis and I spent a day driving around L.A. to shoot some new B-roll, now that different scenes needed a sense of continuity as being connected by the city.

Promoting Coffee House Chronicles: The Movie with producer Alan Reade, writer-director Stewart Wade, and actor John Suazo.

Based on a draft version of the film, Stewart and I finalized a combination VOD and DVD distribution deal with Dekkoo and TLA Releasing. And then the game of promotion started all over again. “Remember the web series? It’s now a film! With brand new content!“

I think if I’d known from the beginning that the web series would definitely become a film, Stewart and I could have made different kinds of decisions earlier about storyboarding and continuity and certainly deciding which characters we would extend to create a kind of story wrapper around the other episodes. We might have made exactly the same decisions but definitely shot some scenes more efficiently, such as over two days in a row instead of almost a year apart, which meant taking time to schedule the same actors and crew as they finished other projects. Having to retrofit the story to conform better to the conventions of narrative film is more difficult and expensive than simply doing it in the planning stages forward.

My experience so far is that overall it’s easier to market and promote a film than it is to market and promote a web series. With a web series, until it is complete, you are always selling potential viewers and fans on what’s next or what’s about to be next. You’re asking interested people to follow along on a journey of months or years. Once you have a finished film, though, it does make it easier to get reviews and sales because you’re promoting one finished thing, even if that one thing is multifaceted. Both approaches have their advantages, and web series are terrific ways to build new audiences. However, the sales and marketing world for produced content still seems geared toward films as its standard unit.

All content creation involves different kinds of marathons and sprints. In our case having a film seems to be putting us in a larger market for the marathon part of things. But we will always be grateful to the web series format for allowing us to build an audience, one sprint at a time.

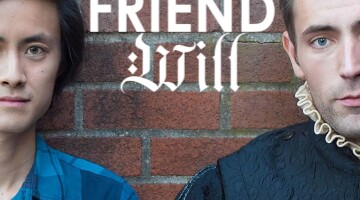

Darryl Stephens and Drew Droege on the cover of the Coffee House Chronicles: The Movie DVD.

- VOD: https://dekkoo.vhx.tv/coffee-house-chronicles-the-movie

- DVD: https://www.amazon.com/Coffee-House-Chronicles-Cameron-Ferguson/dp/B07737S76K

No Comment